Every military intelligence organization faces the same fundamental challenge: their most valuable insights often sit trapped in disconnected systems that cannot talk to each other. A classified signal intelligence report lives in one database, human intelligence sits in another, and open source intelligence resides in a completely separate environment. Meanwhile, adversaries operate without such artificial boundaries.

This fragmentation costs intelligence teams precious time and operational effectiveness. Analysts waste hours manually searching multiple systems, copying information between platforms, and attempting to correlate insights that should flow together naturally. The problem goes beyond inconvenience; it creates dangerous intelligence gaps where critical connections remain undiscovered.

The U.S. Intelligence Community’s 2024-2026 OSINT Strategy explicitly addresses this challenge, emphasizing data sharing and integration as core priorities. However, translating strategy into operational reality requires overcoming technical barriers, security concerns, organizational resistance, and deeply embedded cultural assumptions about how intelligence should work.

Why Intelligence Integration Fails in Military Organizations

The roots of intelligence fragmentation run deep. Military and intelligence organizations built their classified systems decades ago, long before modern data integration technologies existed. These legacy platforms were designed for specific collection disciplines, each with its own security requirements, data formats, and user interfaces.

Security classification creates the most obvious barrier. Classified intelligence systems require strict access controls, air-gapped networks, and compartmented information handling. These necessary security measures make it technically difficult to integrate classified systems with open source platforms that operate on different networks with different security requirements. The fear of classified information leaking into lower-classification environments leads many organizations to maintain complete separation between systems.

This separation, while understandable from a security perspective, creates significant operational problems. Consider a targeting analyst preparing an intelligence package. They might need to consult signals intelligence for communications patterns, human intelligence for insider information about leadership intentions, geospatial intelligence for terrain analysis, and open source intelligence for contextual understanding of local dynamics. If each type of intelligence lives in a separate system, the analyst must log into multiple platforms, search each independently, and manually compile findings into a coherent assessment.

Data format incompatibility compounds integration challenges. Different intelligence systems use different schemas, metadata standards, and data structures. A report from one system might identify entities using one naming convention while another system uses completely different identifiers for the same individuals or organizations. Entity resolution across systems becomes a manual, error-prone process.

Organizational culture presents perhaps the most stubborn barrier to intelligence integration. Many intelligence professionals grew up in environments where OSINT was considered supplementary to “real” classified intelligence. This mindset persists in some organizations despite overwhelming evidence that open source information often provides critical context, early warning indicators, and unique insights unavailable through classified channels.

Different intelligence disciplines also maintain distinct analytical cultures and methodologies. Signals intelligence analysts approach problems differently than imagery analysts, who work differently from OSINT investigators. These different approaches are valuable, but without integration, they can lead to parallel analytical efforts that never converge into unified intelligence products.

The Strategic Cost of Intelligence Silos

Fragmented intelligence systems impose costs that extend far beyond analyst frustration. These costs manifest in delayed decision-making, missed intelligence connections, and reduced operational effectiveness.

Time represents the most immediate cost. In modern conflicts, intelligence value often has a short half-life. Information that would enable effective action today becomes useless tomorrow. When analysts spend hours searching multiple systems and manually correlating information, by the time they produce finished intelligence, the operational window may have closed.

Incomplete threat pictures pose a more dangerous risk. Adversaries do not limit themselves to activities visible through a single collection method. A sophisticated threat actor might use encrypted communications monitored by signals intelligence, meet in person creating opportunities for human intelligence collection, and simultaneously conduct social media influence campaigns visible through OSINT. If intelligence teams cannot integrate insights from all these sources, they see only fragments of adversary operations.

This fragmentation becomes particularly problematic when tracking criminal networks or terrorist organizations that operate across multiple domains. A financial investigation might reveal suspicious transactions through open source financial records, while classified intercepts provide communications intelligence about the same network. Without integration, analysts might not realize they are tracking the same targets, missing opportunities for coordinated operations.

Resource waste represents another significant cost. Multiple analysts in different units often investigate the same targets or questions independently because they lack visibility into each other’s work. This duplication consumes valuable analytical capacity that could address other intelligence gaps.

Technical Approaches to Intelligence Integration

Despite formidable challenges, several technical approaches enable effective integration between classified and open source intelligence systems while maintaining appropriate security boundaries.

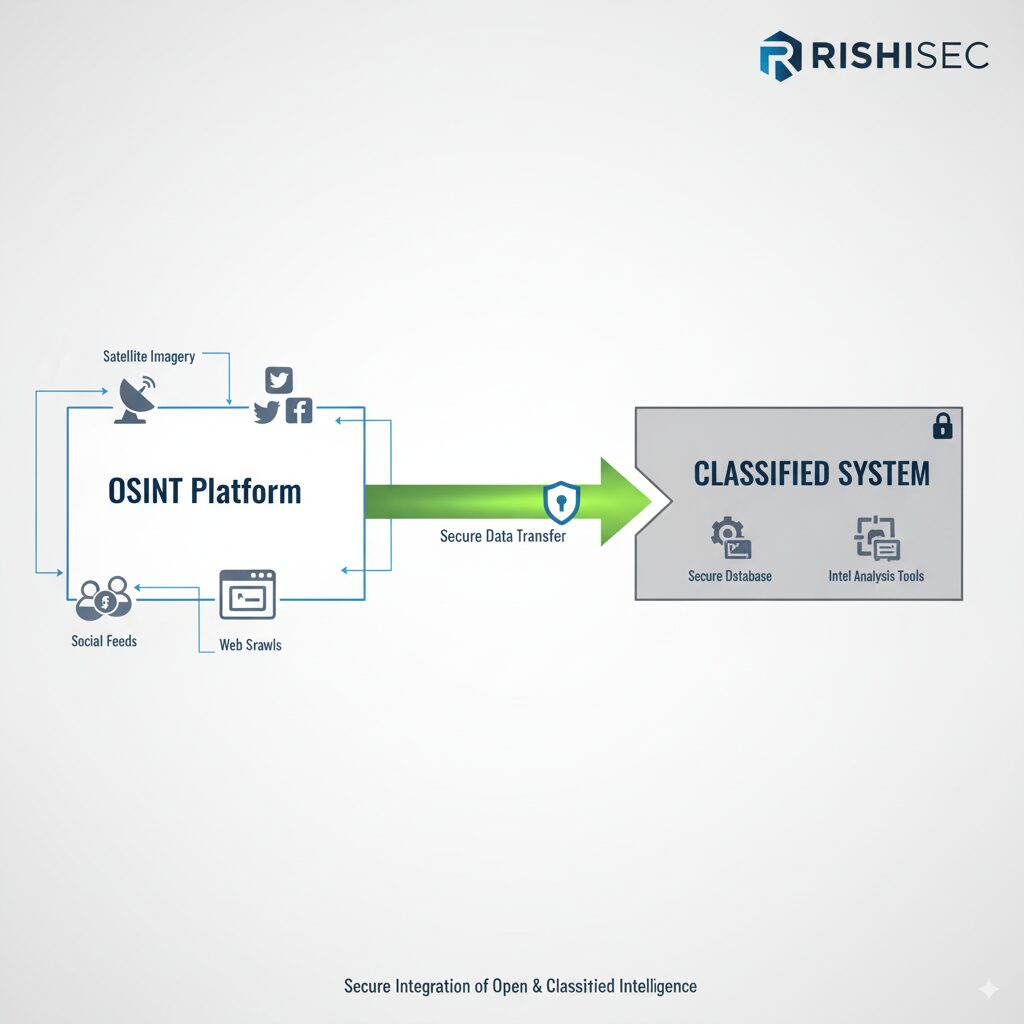

One-way data flows provide the foundation for secure integration. In this model, classified systems can pull in selected OSINT feeds while preventing any information from flowing back to lower-classification networks. This approach satisfies security requirements while giving classified-side analysts access to open source intelligence without leaving their secure environment.

Modern platforms like Kindi can operate in this architecture, providing OSINT collection and analysis capabilities that feed results into classified intelligence systems through secure, unidirectional data transfers. This allows military intelligence teams to leverage AI-powered OSINT automation and link analysis while maintaining strict classification boundaries.

API-based integration offers flexibility for organizations with modern IT infrastructure. Rather than requiring direct system connections, APIs allow different intelligence platforms to exchange specific data elements through well-defined interfaces. This approach maintains system independence while enabling selective integration where appropriate.

Standardized data formats reduce integration friction. When multiple intelligence systems use common schemas for representing entities, relationships, and events, cross-system analysis becomes more feasible. Efforts like the Structured Threat Information Expression (STIX) framework provide models that different systems can adopt to improve interoperability.

Key Technical Requirements for Intelligence Integration

- Security-first design: Every integration approach must prioritize protection of classified information. This includes network separation, access controls, audit logging, and technical measures to prevent unauthorized data flows.

- Entity resolution capabilities: Systems must identify when different data sources reference the same individuals, organizations, or events despite using different names or identifiers. This requires sophisticated matching algorithms that account for name variations, aliases, and transliteration differences.

- Metadata standardization: Integrated systems need consistent ways to tag, classify, and describe information. This includes temporal data, geospatial coordinates, source reliability ratings, and collection method indicators.

- Analytical workflow integration: Beyond data sharing, systems should support integrated analytical processes where analysts can work across different intelligence types without switching between disconnected tools.

- Performance at scale: Integration solutions must handle the volume and velocity of modern intelligence operations. This means processing thousands of intelligence reports, millions of open source documents, and billions of data points without creating analytical bottlenecks.

Cloud technologies offer new opportunities for intelligence integration while introducing new security challenges. Cloud-based intelligence platforms can provide better scalability, easier updates, and more flexible integration options than traditional on-premise systems. However, military organizations must carefully evaluate cloud security, data sovereignty, and availability concerns before moving intelligence operations to cloud environments.

Organizational Changes Required for Successful Integration

Technology alone cannot solve intelligence integration challenges. Successful integration requires organizational changes that address cultural barriers, workflow processes, and personnel training.

Leadership commitment represents the essential first step. Senior intelligence officers must champion integration efforts, allocate resources, and send clear signals that integrated intelligence production is an organizational priority. This includes setting integration metrics, rewarding personnel who develop cross-discipline expertise, and reforming processes that reinforce stovepipes.

Cross-functional intelligence teams provide organizational structures that support integration. Rather than maintaining separate OSINT, signals intelligence, and imagery analysis units, organizations can create integrated teams where specialists from different disciplines collaborate on shared intelligence problems. This approach breaks down cultural barriers and creates opportunities for informal knowledge sharing that formal systems cannot provide.

Standardized analytical processes help ensure integration occurs consistently across the organization. This includes common templates for intelligence products, shared terminology for describing threats and targets, and standardized procedures for corroborating information across different sources. When every analyst follows similar processes, their outputs integrate more easily.

Information sharing policies require careful attention. Organizations must define clear rules about what information can flow between different security domains, who has authority to approve data transfers, and how to handle situations where integration reveals security concerns. These policies should enable appropriate sharing while maintaining security.

Real-World Integration Success Stories

Despite challenges, several military intelligence organizations have achieved meaningful integration between OSINT and classified systems, demonstrating that success is possible with the right approaches.

Some units have implemented “fusion cells” where analysts with clearances work in classified environments while having access to OSINT tools and feeds. These analysts can pull open source intelligence into their classified analysis without creating security risks. This approach provides immediate integration benefits while waiting for more comprehensive technical solutions.

Other organizations have used “tearline” approaches where OSINT analysts produce intelligence products that can be shared with classified-side counterparts. While this requires manual handoffs, it creates valuable information sharing without requiring complex technical integration. The key is ensuring tearline products include sufficient detail and context to be useful in classified analysis.

Forward-deployed intelligence teams often drive integration innovation. Operating in demanding environments with urgent intelligence requirements, these teams cannot afford the inefficiencies of fragmented systems. They develop pragmatic solutions that balance security requirements with operational necessity, and their innovations often influence enterprise-level integration efforts.

Automation technologies have proven particularly valuable in integration efforts. Platforms that automatically collect, process, and categorize OSINT can feed structured intelligence products into classified systems without requiring constant manual intervention. This reduces the personnel burden of maintaining integration while improving the timeliness and consistency of information sharing.

Best Practices for Intelligence Integration Implementation

Organizations embarking on intelligence integration initiatives should follow proven practices that increase the likelihood of success while avoiding common pitfalls.

Start with pilot programs rather than enterprise-wide implementations. Select a specific use case, perhaps a particular threat or geographic area, and implement integration for that limited scope. This approach allows organizations to learn, adjust processes, and demonstrate value before scaling to larger implementations. Successful pilots build organizational support and provide concrete examples that overcome skepticism.

Focus on high-value integration points rather than attempting to integrate everything. Not all intelligence needs to be integrated. Organizations should identify where integration provides the greatest operational benefit and prioritize those areas. Target development, threat tracking, and operational support often represent high-value integration opportunities.

Involve end users throughout the implementation process. The analysts who will actually use integrated systems should help design workflows, provide feedback on prototypes, and participate in testing. Systems designed without user input often fail to meet operational needs, leading to low adoption rates and wasted investment.

Establish clear metrics for measuring integration success. These might include time saved in analytical processes, number of cross-discipline intelligence products produced, or operational outcomes enabled by integrated intelligence. Metrics help demonstrate value to leadership and identify areas needing improvement.

Plan for continuous evolution rather than one-time implementation. Intelligence integration is not a project with a defined endpoint but an ongoing process of improvement. Technology changes, threats evolve, and organizational needs shift. Integration approaches must adapt accordingly, requiring sustained investment and attention.

| Integration Challenge | Technical Solution | Organizational Solution | Expected Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Security Classification Barriers | One-way data flows, cross-domain solutions | Clear information sharing policies, security training | 6-12 months |

| Data Format Incompatibility | API integration, standardized schemas | Cross-functional data governance teams | 3-9 months |

| Cultural Resistance to OSINT | Demonstrable OSINT success stories | Leadership advocacy, integrated teams | 12-24 months |

| Legacy System Limitations | Middleware, data extraction tools | Modernization roadmap, phased replacement | 18-36 months |

| Entity Resolution Across Systems | AI-powered matching algorithms | Standardized naming conventions, analyst training | 6-12 months |

The Role of Modern OSINT Platforms in Intelligence Integration

Advanced OSINT platforms play a crucial role in intelligence integration by providing the connective tissue between open source and classified intelligence environments. These platforms must offer specific capabilities that facilitate integration while respecting security boundaries.

Automated data collection and processing reduce the manual effort required to bring OSINT into classified analysis. Rather than requiring analysts to manually search dozens of open sources, modern platforms can continuously monitor relevant sources, extract pertinent information, and deliver structured intelligence products ready for integration into classified systems.

Link analysis capabilities prove particularly valuable for integration. When OSINT platforms can automatically identify relationships between entities, events, and activities in open source data, they create network diagrams and analytical products that complement classified intelligence collection. Analysts can overlay open source network analysis onto classified intelligence, revealing connections that neither source would show independently.

Platforms like Kindi provide these integration-enabling capabilities through AI-powered automation that handles the heavy lifting of OSINT collection and analysis. The platform can operate in secure environments, feeding intelligence products through one-way connections into classified systems while maintaining appropriate security posture. This approach gives military intelligence teams access to sophisticated OSINT capabilities without compromising classified information security.

Collaboration features within OSINT platforms support organizational integration even when technical system integration faces obstacles. When multiple analysts can work within the same OSINT platform, sharing findings and building collective understanding, they achieve integration at the human level that complements technical system integration.

Export capabilities determine how effectively OSINT platforms can feed intelligence into other systems. Platforms should support multiple output formats, provide rich metadata with exports, and enable automated delivery of intelligence products to downstream systems. This flexibility ensures OSINT can integrate with diverse classified intelligence architectures.

Emerging Technologies and Future Integration Approaches

Several emerging technologies promise to transform intelligence integration over the coming years, offering new solutions to longstanding challenges.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning will enable more sophisticated automated correlation between open source and classified intelligence. Rather than requiring analysts to manually identify connections, AI systems will continuously analyze both types of intelligence, flagging potential correlations for human review. This capability will dramatically increase the speed and completeness of integrated analysis.

Zero-trust security architectures may provide new approaches to intelligence integration. Rather than relying primarily on network segmentation to protect classified information, zero-trust models implement granular access controls at the data element level. This could enable more flexible integration while maintaining security, as systems could share specific pieces of information based on user clearances and need-to-know without requiring complete network separation.

Blockchain and distributed ledger technologies offer potential solutions for audit logging and data provenance tracking in integrated systems. When intelligence flows between multiple systems, understanding its origin and tracking who accessed it becomes critical for security. Blockchain-based audit trails could provide tamper-proof records of intelligence handling across integrated environments.

Quantum computing presents both opportunities and challenges for intelligence integration. On one hand, quantum systems could enable much faster analysis of massive integrated datasets. On the other hand, quantum capabilities may threaten current encryption methods, requiring new approaches to securing intelligence systems and the connections between them.

The proliferation of edge computing could change where and how intelligence integration occurs. Rather than requiring all integration to happen in centralized facilities, edge systems could perform preliminary integration at forward locations, closer to operations. This distributed approach might reduce latency and improve operational support while introducing new security considerations.

Overcoming Resistance to Integration

Even with perfect technical solutions, intelligence integration efforts often fail due to organizational resistance. Understanding and addressing this resistance represents a critical success factor.

Many intelligence professionals worry that integration will reduce their discipline’s importance or reveal gaps in their analytical capabilities. This fear is understandable but misguided. Integration does not diminish individual collection disciplines; it amplifies their impact by providing context and correlation that increases the value of all intelligence sources.

Some organizations resist integration due to concerns about information security. These concerns deserve serious attention, but they should drive the development of secure integration solutions rather than serving as reasons to maintain complete separation. The security risks of integration must be balanced against the operational risks of fragmentation.

Budget and resource constraints often slow integration efforts. Implementing technical solutions, training personnel, and changing processes require investment. However, organizations should consider the opportunity costs of not integrating. How many intelligence failures result from fragmented systems? How much analyst time is wasted on manual correlation? These hidden costs often exceed the visible costs of integration.

Successfully overcoming resistance requires demonstrating tangible value. When analysts see that integration makes their jobs easier, produces better intelligence, and enables operational success, they become advocates. Starting with small, successful integration efforts builds this momentum more effectively than top-down mandates.

Conclusion

Intelligence integration represents one of the most important challenges facing military intelligence organizations today. The artificial separation between open source and classified intelligence creates gaps that adversaries exploit. In an era where threats move seamlessly across domains and information environments, intelligence systems must provide similar integration.

Solving this challenge requires both technical and organizational solutions. Modern integration technologies provide the tools needed to connect disparate systems securely. However, technology alone cannot overcome cultural barriers, organizational silos, and entrenched processes that reinforce fragmentation.

Successful integration demands leadership commitment, user involvement, appropriate security measures, and sustained investment. Organizations must balance security requirements with operational necessity, implementing integration approaches that protect classified information while enabling the analytical workflows that produce actionable intelligence.

The military intelligence organizations that master integration will gain significant advantages. They will detect threats faster, understand adversary operations more completely, and provide commanders with the comprehensive intelligence needed for effective decision-making. Those that maintain fragmented systems will find themselves increasingly unable to keep pace with adversaries who face no such limitations.

Ready to bridge the gap between your OSINT and classified intelligence operations? Discover how Kindi provides secure, AI-powered OSINT capabilities that integrate seamlessly into your intelligence architecture. Want to build your team’s integration expertise? Explore our OSINT courses for hands-on training in modern intelligence operations and analytical techniques.

FAQ

Can OSINT and classified intelligence systems be directly connected?

Direct bidirectional connections between OSINT and classified systems are generally not feasible due to security requirements. However, one-way data flows allow classified systems to pull in OSINT feeds without creating security risks. Cross-domain solutions provide another option for controlled information sharing between security domains. The key is implementing integration approaches that enable information sharing while maintaining appropriate security boundaries and preventing classified information from flowing to lower-classification networks.

What are the biggest barriers to intelligence integration in military organizations?

Security classification requirements create technical barriers, while organizational culture and legacy systems create operational barriers. Many intelligence professionals grew up in environments where different collection disciplines operated independently, creating cultural resistance to integration. Legacy systems built decades ago often lack modern integration capabilities. Additionally, concerns about information security, budget constraints, and the complexity of changing established processes all contribute to integration challenges.

How long does it take to implement intelligence integration?

Implementation timelines vary significantly based on scope and approach. Pilot programs focusing on specific use cases can demonstrate value within three to six months. More comprehensive integration efforts typically require 12 to 24 months for technical implementation, organizational change, and user adoption. However, intelligence integration should be viewed as an ongoing process rather than a one-time project, requiring continuous refinement as technologies evolve and organizational needs change.

Do analysts need special training to work with integrated intelligence systems?

Yes, effective use of integrated systems requires cross-discipline knowledge that many analysts do not receive in traditional training programs. Analysts need familiarity with multiple collection disciplines, understanding the strengths and limitations of each. They should know how to correlate information from different sources, resolve entity references across systems, and produce intelligence products that synthesize insights from multiple disciplines. Organizations should invest in training programs that develop these cross-discipline analytical skills.

What metrics should organizations use to measure integration success?

Effective metrics include both process and outcome measures. Process metrics might track time saved in analytical workflows, number of systems analysts must access to complete tasks, or percentage of intelligence products that incorporate multiple collection disciplines. Outcome metrics could measure operational impacts like decision-making speed, threat detection rates, or commander satisfaction with intelligence support. Organizations should establish baseline measurements before integration and track improvements over time to demonstrate value and identify areas needing further refinement.